"In Montenegro, dreams come true, making it a gateway of desires"

A Belarusian woman bravely shares her gripping tale of forging a new life far from her homeland.

Meet Natalia Masyuk, a mother of four, who found herself in the Land of the Black Mountains after her homeland turned hostile. She bared her heart to "Solidarnasc" in two, poignant interviews—the first in 2022, and the second three years later.

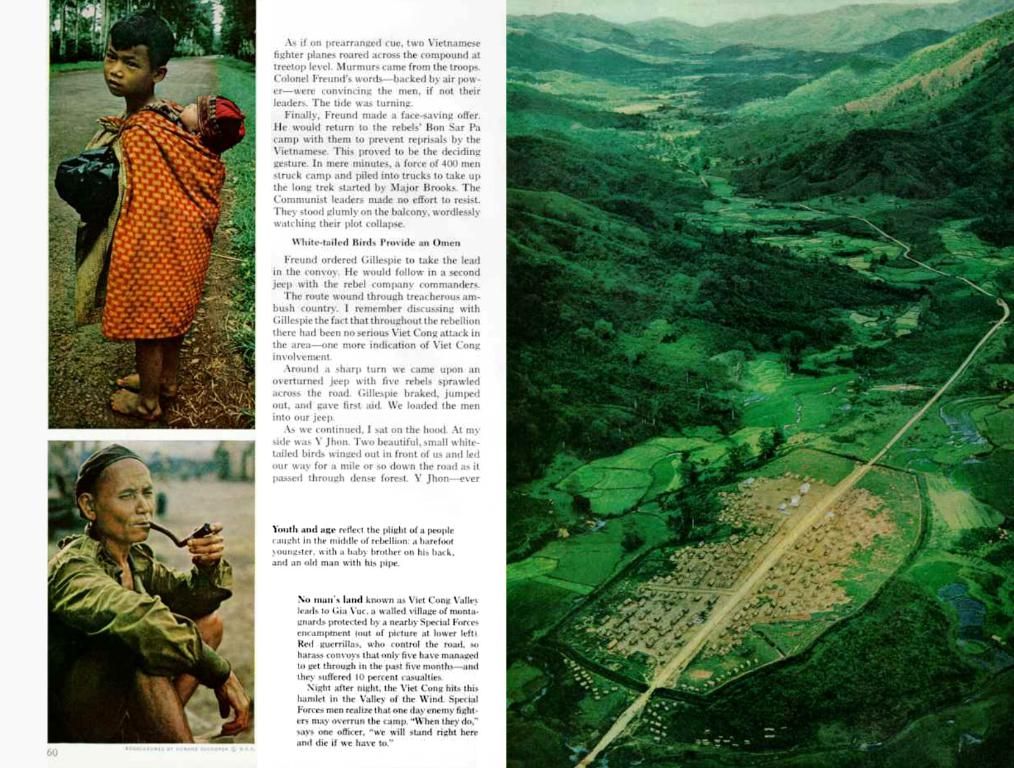

Natalia's journey began in earnest following the August 2020 elections, when she became an active participant in anti-violence protests and negotiations with local authorities. Much like many activists, she fell under the watchful eye of the KGB and Investigative Committee, subjected to interrogations, searches, and device seizures.

- I was part of the "Sход" platform. In August 2021, sweeping raids on participants began, and I was caught in the storm. In December of the same year, "Sход" was labeled an "extremist organization."

Despite her resolve to remain in Belarus, she felt the pressure mounting.

- I kept insisting: why should I leave? Let those who despise me depart. I long for my country to thrive, and if we all abandon it, how can it? We must stand ground, fight, and do everything we can.

The future of her children was foremost in her mind – they were about to embark on their first year of school. She fretted over her children silently marching in line as the national anthem rang out at their school.

- Military-patriotic education, priests in educational institutions... It's not the future I envision for my children.

When their organization was declared "extremist," her husband persuaded her to flee to avoid potential criminal charges.

- He said: You realize they'll arrest you, you won't make a "confession" video, you'll languish in prison and they'll seize our children. It's easier to leave.

In one, fateful night, their fate was set. She pledged allegiance to her children and exiled to Montenegro.

Devoid of a Schengen visa, she and her children decided to fly to Istanbul and then to Podgorica.

Before setting off, Natalia penned an appeal to the People's Embassy of Montenegro, pleading for their assistance upon her arrival.

- The locals rallied to her aid. I was greeted by Belarusian expats. Upon arriving in Bar, I knew I had found my new home. It reminded me of my hometown.

The children swiftly acclimated to their new surroundings.

- The younger ones adjusted easily to the kindergarten here, picked up the language. They have no language hurdles at school. The older ones grappled harder with the transition.

Natalia's son Lubomir found it particularly difficult to adapt to school, showing signs of ADHD. The school assigned him a tutor to help him grasp the curriculum, and a psychologist's evaluation was not required. The pedagogical commission justified this by stating that the child struggled with learning the Montenegrin language.

- With the tutor, the child began to improve. School assignments became less daunting. If assistance is needed in the future, we will require a psychologist's recommendation for classroom support.

"Montenegro is akin to an open gateway, where dreams come true. Just don't stand still."

In Belarus, Natalia honed her craft as a lawyer using her second degree. In Montenegro, she could channel her first degree in choreography by opening a dance studio.

- I hadn't practiced choreography for a decade, and I grappled with insecurities and complexes. The opportunity dictated everything. I took my son to the dentist and told her I might try my hand at choreography. She advised me to open my own studio so I wouldn't be reliant on others. Make it compact, yet your own.

She drew inspiration from this encounter, imagining an open portal for dreams to materialize. With a dash of persistence, she embarked on her quest.

She secured her first students – children.

- The movements came back to me instinctively.

Then, body ballet classes took flight – even women reclaimed their confidence, regaining their footing.

One day, she pondered, "Why aren't there any Belarusians or signs of our existence here? I wanted to make our presence known and introduce Montenegrins to us. And what better way to do that than through dance!"

Thus, the idea of forming a Belarusian dance ensemble was born.

Crafting a Belarusian dance troupe may seem presumptuous, but she proclaimed, "I am organizing a Belarusian dance ensemble that will showcase our culture, as I stated in the first announcement."

One of the first to join the troupe was Natalia, a Belarusian language teacher who only speaks Belarusian. Though not all group members are Belarusians, they comprehensively grasp her instructions.

Natalia grapples with dance, yet she persists with unwavering determination. Her small stature belies her immense determination, which often leaves Natalia feeling sheepish when she falters.

Recruiting for the ensemble was a tough slog, but she was steadfast in her pursuit. Her objective was to craft a small repertoire with 3-4 numbers and participate in one of the numerous folklore festivals in Montenegro to attract attention, demonstrate the ensemble's potential, and forge a name for themselves.

In a mere few months, the Belarusian dance ensemble "Valoshki" took to the stage at a festival in Montenegro and garnered first place in their age category.

- We tailored our costumes ourselves, adorned them at night. We lacked shoes because they're pricey. We danced in ballet flats. I managed to find a Russian artisan in the region who crafted us Belarusian belts.

By the way, the ensemble's participants hail not only from Belarus but also Ukraine and Russia.

The previous year, they hosted a Belarusian Culture Day in Budva and organized their own concert.

After their performances, a Belarusian patron approached her, asking, "What do you require now?" I said, "We're in ballet flats and can't afford shoes." He inquired about the funds required and offered his support.

Can Belarusians in Montenegro receive international protection?

This lingering question gnaws at Natalia, as it does for many other Belarusians in Montenegro.

Natalia has obtained a residential permit, valid for a year.

- From my third residence permit, I declined as I applied for international protection. Last year, when persecutions for participating in the Coordination Council began in Belarus (Natalia was a member of the second convocation — ed. note), a search was conducted at my home in Slutsk, and my property—a plot with an unfinished house and an apartment—was confiscated.

The Investigative Committee addressed her request for the reasons behind this action, citing her suspected involvement in crimes under part 1 of article 357 (conspiracy or other actions committed with the aim of seizing or retaining state power unconstitutionally) and part 3 of article 361-1 of the Criminal Code (creation of an extremist formation or participation in it). The first article carries a punishment of up to 12 years imprisonment.

At her initial interview at the Department for Refugee Status of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, they warned her not to expect international protection, as she had resided in Montenegro for three years without seeking asylum. They maintained that she had utilized her passport, which indicated she had no fear, and, if it weren't for Lukashenko's decree, she would have continued to use it despite the persecutions in her home country. Thus, her apprehensions were mere fabrications – their viewpoint on her situation. They claimed she should have applied for asylum upon setting foot in Montenegro, at which point her case would have been taken seriously.

Legal experts working with asylum applicants explained to Natalia that Montenegro is not eager to grant asylum to anyone. In April of this year, nine months after submitting her application, Natalia received a rejection of international protection. The Belarusian woman appealed the decision in court, but her case remains unresolved.

- The rejection was ten pages long, detailing how I fabricated my own fears. The letter from the Belarusian Investigative Committee went unacknowledged in the entire document.

Prior rejections of asylum applications closely mirrored hers – identical in wording, length, and content.

They contend that everything is hunky-dory in Belarus, the economy is booming, and democracy is progressing, based on documents dating back to 2016.

According to Natalia, following Lukashenko's decree barring Belarusians from procuring passports overseas, the Belarusian diaspora in Montenegro embarked on various initiatives to secure their protection and legalization.

I penned approximately twenty missives to assorted institutions (parties, ministries, departments), describing our plight and requesting assistance in resolving our legalization issue – enabling us to secure international protection, much like Ukrainians do.

I received responses solely from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Internal Affairs: this is not our domain; kindly direct your inquiry elsewhere.

There are few Belarusians in Montenegro. We merely seek protection and the right to live legally within your country.

Several Belarusians leave and attain visas, though Natalia remains unable to acquire a Schengen visa. Her husband works in the EU and visits them sporadically, but his work visa hinders their ability to jointly seek visas.

Natalia contemplates her next moves, as her passport expires in August.

- It's like experiencing a Spanish sense of shame. Why is this happening in our country?

Three years ago, I posed the question to Natalia about her thoughts on not returning to Belarus.

- Yes, I have pondered that possibility. I assume our return is imminently delayed. I feel as though I'm still in Belarus. I read Telegram channels, I'm emotionally invested in my homeland, and I weep often.

Perhaps we've all been hardened by injustice. But when sheer foolishness or cruelty emerges... It's like experiencing a Spanish sense of shame. Why is this transpiring in our country?

Yet, I understand that the outside world may not fully grasp the situation. Those who left not only yearn for Belarus and aspire to aid it, but also must adapt and thrive in their newfound home. Because you are responsible for your life and the welfare of your children in a foreign land. When you lack a command of the language, lack steady employment...

The woman who guided me through the prerequisites stated bluntly: there's no work here. It was a solemn declaration. If you wish to survive, find employment here yourself.

Lies propagate that we merely crave a simpler life or dream of a quick return.

I believe everyone, much like me, departed Belarus aware that life overseas wouldn't be easy, that we'd need to make do, that our long-valued careers and earnings would not be recognized in foreign lands. All begins anew here.

Those who left Belarus were thoughtful individuals who could have contributed significantly to building and creating prosperity.

- With sadness, I must admit that we are non-returners. My children flourish in Montenegro. The mountains, the sea – they yearn for no other landscapes. They claim we'll visit Belarus as tourists, but we'll live here.

Sources:

- Charter97.org

- BelNPB

- Natalia Masyuk, despite her strong ties to Belarus, found herself seeking asylum in Montenegro due to the political climate back home.

- As an emigrant in Montenegro, Natalia has transitioned from her career as a lawyer to opening a dance studio, demonstrating a shift in her lifestyle and focus on education-and-self-development.

- Natalia's journey has also taken her into the realm of politics, as she advocates for the Belarusian diaspora in Montenegro, seeking international protection and legalization amidst ongoing challenges and rejections.